Carl R. Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedman’s Savings Bank (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976).

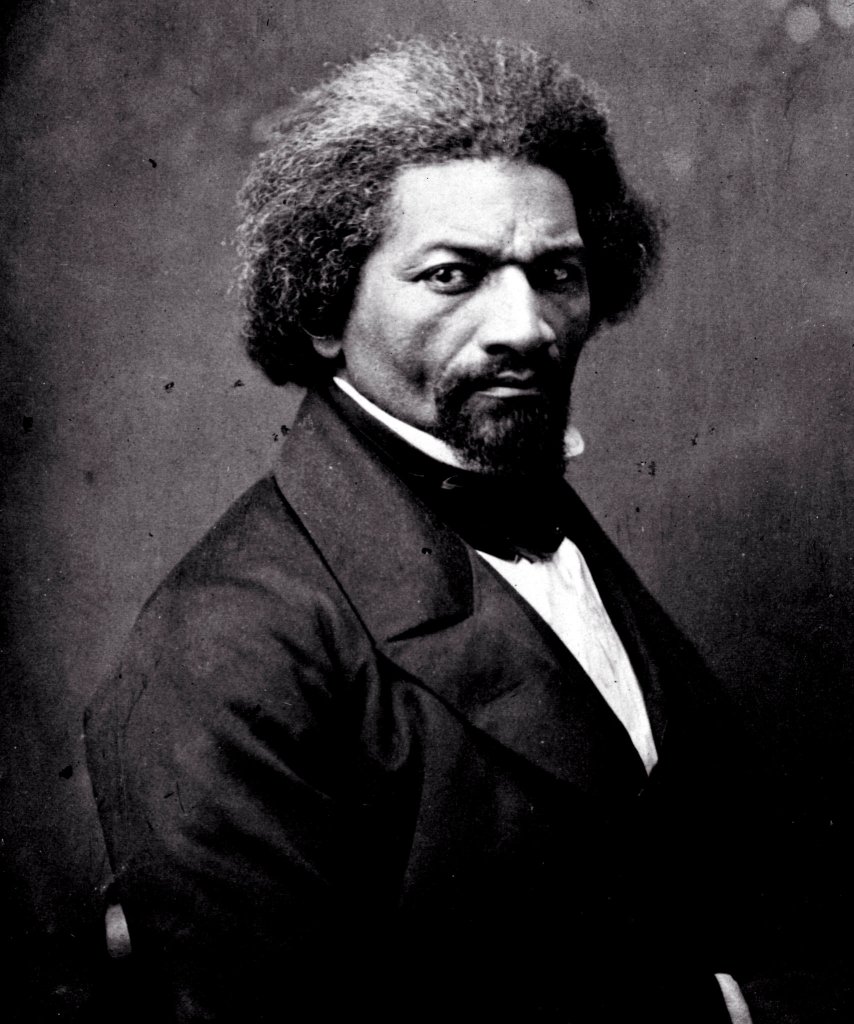

“This bank is just what the Freedmen need” said Abraham Lincoln on March 3, 1865, when the bill chartering the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company was signed into law. Yet, by the time it was all over, Frederick Douglass would say that “the Freedman’s Bank was the black man’s cow but the white man’s milk” (Frederick Douglass to Gerrit Smith, July 3, 1874, Smith MSS, Syracuse University Library, in Osthaus, 1).

W. E. B. Du Bois gives a brief survey of this episode in his Black Reconstruction and sums it up like this: “No more extraordinary and disreputable venture ever disgraced American business disguised as philanthropy than the Freedmen’s Bank—a chapter in American history which most Americans naturally prefer to forget” (Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (Oxford, 2007), 491).

In 1976, Carl Osthaus published his dissertation on the Freedman’s Bank, which he completed at the University of Chicago under his mentor John Hope Franklin. The book is a superb study enabling us to not forget. His detailed, meticulous account tells both the story of the Freedman’s Bank as well as as the broader movements in America during Reconstruction.

The Freedman’s Bank and Racial “Uplift”

The Freedman’s Bank is a powerful illustration of dynamics that were taking place throughout the country, involving every sphere of society:

“Just as the Freedmen’s Bureau would seek to satisfy the ex-slaves’ need for land, education, and immediate relief, and the Christian missionaries would care for the reformation of their souls, the Freedman’s Bank would instill economic morals and social values in the Negroes”

Osthaus, 10.

I found particularly fascinating the role of northern missionaries, white and Black, in promoting the bank, and the way moral and spiritual “uplift” was intertwined with the material operations of the Bank:

“Every piece of Freedman’s Bank literature revealed the officers’ missionary zeal. Bank officials incessantly distributed, in D. L. Eaton’s words, ‘tracts and papers… on temperance, frugality, economy chastity, the virtues of thrift & savings; explaining how daily savings in small sums at interest will accumulate & the duty of men to provide for their families–and in a word giving short & simple homilies on the virtues which constitute the moral life of civilized communities'”

Eaton to Committee on Freedmen’s Affairs, July 5, 1868, Committee on Freedmen’s Affairs, National Freedman’s Savings and Trust Co., Legislative Records, NA, RG 233, in Osthaus, 49.

Osthaus does not shy away from describing the paternalism that infused some of the efforts on behalf of the bank:

“Bank officials spoke with egalitarian rhetoric, although sometimes their actions and comments displayed paternalistic attitudes… A circular intended for the freedmen would, they erroneously believed, “of course” be referred “for advice to those more intelligent whom they have been accustomed to trust.” Other statements were not so subtly condescending. The Memphis cashier declared that “the fickel [sic] mindedness of the Colored people makes it impossible for me to remit to you yet the small sum I have as yet on deposit.”

Osthaus, 70–71.

Cooke, Railroads, and Banks

The original reason I was drawn to look at the Freedman’s Bank was the role of Jay Cooke, his brother Henry Cooke, and the way the massive enterprise of trans-continental railroads affected the entire country. Osthaus tells the story of the Cookes and the Bank in full:

“The name of Jay Cooke, the famous Civil War financier, appeared frequently in Bank advertisements, although he had no connection with the Bank and was associated with it only tangentially because his brother and business partner Henry D. Cooke, became chairman of the Finance Committee in mid-1867. That the Cookes had no connection with the Bank before 1867 did not prevent the Semi-Weekly Louisianian from praising their roles in its establishment. Later Bank officials used the Civil War fame of Jay Cooke specifically to bolster confidence in the Bank’s investment policy and generally to highlight the Bank’s sound financial standing”

Osthaus, 55.

Ironically, the Cookes would take advantage of the Freedman’s Bank as their own banking and investment institutions came under severe strain in the early 1870s. At one point, Henry Cooke transferred $500,000 from the Freedman’s Bank to the First National Bank (which they controlled):

“$500,000 [was] an enormous sum on which the Cookes paid only 5 percent interest, while the Freedman’s Bank was paying its depositors 6 per- cent”

Osthaus 153–54.

This was a pattern in the management of the bank:

“This episode reveals a significant pattern: Cooke, Huntington, and other officers and trustees on occasion used the Freedmen’s Bank as a dumping ground for their bad private claims or the poor securities of the First National Bank”

Osthaus, 156.

When Jay Cooke & Company went bankrupt in 1873, it sent shockwaves through the entire world and triggered a massive recession and the failure of a number of banks, companies, and individuals. The Freedman’s Bank failed at this time, though Osthaus notes that this was not a simple case of cause and effect:

“Obviously no single factor was decisive, and even a combination of fraud and national economic crisis leaves much to be explained”

Osthaus, 173.

Frederick Douglass

As the bank was floundering, they appointed Frederick Douglass to be the president in an effort to prop up its reputation, while keeping important information from him:

“Later it was alleged that Douglass was elected president so that a black man would be in office when the Bank failed. (Fleming, p.85, makes this statement but fails to document it)”

Osthaus, 184.

All along, southerners opposed the bank:

“The most avid purveyors of the conspiracy legend were the southern Democratic newspapers. For years they had regarded the Bank as just another element in the Reconstruction carpetbaggger-missionary complex, and the failure with all its scandalous exposures simply vindicated their judgment”

Osthaus, 202.

Du Bois notes the same thing:

“the white planter regarded the Freedman’s Bank as part of the Freedmen’s Bureau and did everything possible to embarrass it and curtail its growth”

Black Reconstruction, 492.

(As a historiographical note, this southern attitude is reflected in another book on the Freedman’s Bank, Walter Fleming, The Freedmen’s Savings Bank (1927), which I cannot recommend).

Long after it was all said and done, in 1890 Frederick Douglass would assess a number of institutions established to “help” Black people after the Civil War, including the Freedman’s Bank:

“Like the Peabody fund, the Slater fund, the Freedman’s Bank, and many other Institutions, nominally established for the benefit of these people, the hands are white that handle the money. The Germans have a proverb “That they who have the cross will bless themselves,” and there is nothing in the history of the Institutions named, or in the history of others that might be named to contradict this proverb.”

To the Editor of the National Republican, in Frederick Douglass and Philip S. Foner, The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass: Reconstruction and After, vol. IV: Reconstruction and After (New York: International Publishers, 1975), 458).

The story of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company is a fascinating, instructive, and little known episode in American history. Carl Osthaus’s book is a the best and most thorough treatment of it, and I highly recommend it. (There’s a copy available for $2,333 on Amazon–I borrowed it from my public library).

Additional Reading:

- (1876) “Committee on the Freedman’s Bank,” in Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- (1880) United States Senate, Report of the Select Committee to Investigate the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- (1882) Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Park Publishing Company: 487–93

- (1935) W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America (Oxford University Press, 2007): 491–93.

- (2012) Levy, Jonathan. Freaks of Fortune: The Emerging World of Capitalism and Risk in America, chapter 4: “The Failure of the Freedman’s Bank”

- (2017) Baradaran, Mehrsa. The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. Harvard University Press, chapter 1: “Forty Acres or a Savings Bank”

One thought on ““The hands are white that handle the money”: Review of Carl R. Osthaus, Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedman’s Savings Bank”